by Alex Shtaerman

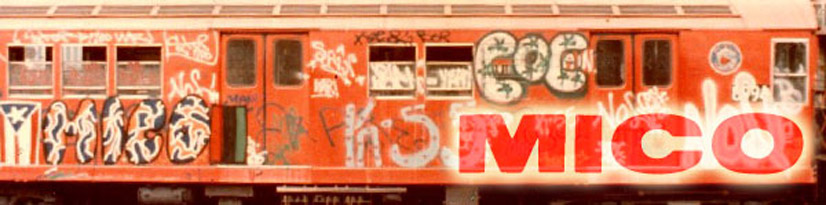

During the ‘70’s and early ’80, a revolution or perhaps an epidemic, depending on one’s personal perspective, swept through New York City’s subway system. Subway cars throughout the city’s vast maze of tunnels, elevated lines and train yards became afflicted by “vandals” who often struck in the darkness of night, writing and spray painting their names on every available inch of railcar real estate; the trains, traveling around the city, would carry their calling cards to millions of bewildered commuters. Over time the names became bigger and bigger, more elaborate, surreal. How could someone illegally paint an entire train car top to bottom with spray paint, completely filling in the windows to the point where it looked as though the car was meant to be a billboard for someone’s namesake as opposed to a sophisticated component within New York City’s famed rapid transit system?

The fact is, it happened, and today some of those same “vandals” are considered legends and pioneers of what is now a flourishing global movement. True, some of those original New York writers who scaled the tallest fences and braved the city’s deepest tunnels have been forgotten, overlooked by history or perhaps simply ill fate, but their legacy continues to live on in back alleys, on street corners, highway underpasses, trains, buses and box trucks, not to mention museums and art galleries around the globe. For some like Joe DeRoche, who was there to take part in New York City’s subway art renaissance, graffiti continues to be a way of life over 30 years later.

As one of the founding members of TPA aka The Public Animals, Joe presides over what at this point in time is the longest lasting and longest running spray paint crew in history. Originally founded in 1976 by Joe, aka JOEY TPA, and two close friends, fellow graffiti writers M3 and VADE, The Public Animals have managed to endure and flourish for over three decades. Today the crew boasts a vast international as well as domestic membership of dedicated artists and aerosol art practitioners. While no longer a practicing graffiti artist (he quit back in ’82!), Joe DeRoche remains at the crew’s apex, inducting new members while staying true to the same values that have kept The Public Animals hungry, no pun intended, since ’76. In a rare glimpse into the true essence of subway art, we catch up with Joe for an in-depth discussion of what it was like to paint your name on a train in New York back in the ‘70’s, and what it all really meant.

Click here to check out our TPA gallery, all pics courtesy of Joe DeRoche and The Public Animals.

RIOTSOUND.COM: You started writing in the early ‘70’s; obviously the decade that preceded the 70’s was a very turbulent time in American history, you had the civil rights movement going on, you had assassinations of multiple leaders, you had a widespread sense of disillusionment among the general public and especially the young people. What was the atmosphere like in New York City during that time and how did it influence you as well as other kids in the ‘70’s to start writing graffiti as a means of self-expression?

JOEY TPA: That is a very deep question and I appreciate it because it’s not the usual crud you get asked. I was born in the very beginning of the ’60’s and came out of the ‘50’s, which was a pretty square and tight environment to grow up in. It wasn’t quite like Happy Days on TV; it was pretty tight-assed due to McCarthyism and other control methods. The ’60’s was the age of “The Revolution” which crossed all borders; women’s lib, the war in Vietnam, racial tensions, and in a place like New York, which is a mecca, you had most of your turbulent reactions starting there. The consequences were felt across the country. But what I recall as really opening me up were the older guys, in their teens and twenties. That’s what sort of gave us, the pre-teens, the impetus to question authority [laughs]. Even some of our parents were wondering what was up and knew it was time for radical change.

RIOTSOUND.COM: So the older generation and even people your parents’ ages were also questioning the status quo and a lot of the things that were happening at the time?

JOEY TPA: Yes, and it was demonstrated through things like unions versus management strikes, recession, oil embargoes, enormous afros, psychedelic clothing, unbridled drug usage, exaggerated clothing like eight inch platform shoes and giant bellbottoms. Everything was larger than life; hair grew really long, deafeningly loud music, dancing in the streets, rampant sex, and graffiti all over the city. Graffiti goes back to the days of the Neanderthal; everybody wanted to write their name on a wall and let people know that they existed and had something to say. Graffiti became a way to voice your opinion. It could have been politically or musically inclined. One would see “Led Zeppelin” across a wall, “Nixon Sucks” or “End the War” among many other slogans and views.

Being a pre-teen in the ’60’s and reaching my teenage years in the ‘70’s, I was definitely impressed by those who were going off to this war that we watched every night on TV, and also [impressed] by people my parents’ age whose kids were the hippies that came out of the ‘50’s. They’re the ones that rebelled against the establishment.

RIOTSOUND.COM: What were the circumstances under which TPA was originally formed? When the crew first came together over 30 years ago, what were your basic goals and aspirations for the crew at that time?

JOEY TPA: Well, 30 years ago would take us back to about 1977; I started writing in ’72. Like any writer, you start out as a toy. At that time, I was hitting park benches, lamp posts, mailboxes and phone booths until I graduated to bigger canvases, which as you can figure was big steel. I hit my first train in ’76. That year I also teamed up with two other guys. The formation of The Public Animals happened in late 1976 with VADE, M3 and yours truly. Rod (VADE) was the oldest of us and he’s always in my mind and in my memory. We were brothers.

We also had a few other guys that came on board like CEY, TON ONE, SPLIT, TE-BOP, and EZO. These are all original members of The Public Animals. We questioned authority and we were thinking about it [like] – well, we’re not doing anything really criminal, but people seemed to think that graffiti was a very wild, undisciplined, vandalistic, and animalistic thing. So [for a crew name] we thought up The Public Animals. I guess the worst thing we did was steal paint. We didn’t destroy personal property either; we kept our escapades limited to public vehicles.

RIOTSOND.COM: So it was satire in a way, the actual name of the crew?

JOEY TPA: Yea, yea, we were sarcastic I suppose. Graffiti writers on the whole are artistic people that are for the most part thumbing their noses at authority and at the establishment. As a general rule, I can’t speak for everyone, graffiti writers are on an artistic bent with an adventurous nature. We are predominantly non-violent, generally perceptive types who sought a way to say we cannot be controlled by the system. If anything violent ever happened, it was usually against a graffiti writer, not by a graffiti writer [laughs]. Of course, there are always exceptions. Gangs got involved and thugs infiltrated crews but as a general rule, a crew wasn’t a gang. A “crew” was usually just a group of guys who wanted to bond together and paint on public property for the public to see.

RIOTSOUND.COM: Now as far as graffiti and Hip-Hop culture goes, I have read several interviews, most recently I read one with Lady Pink where she flat out says that graffiti art and Hip-Hop are only related because they developed and emerged at the same time and therefore were bunched together by the mainstream media. I have also read other comments by writers who just want to be considered artists and don’t feel like their art necessarily has anything to do with Hip-Hop culture. It seems there is almost a degree of bitterness with some of these artists who feel they have been limited by being labeled as part of Hip-Hop. Personally, how do you feel about the whole thing and what is your perspective on graffiti and Hip-Hop culture?

JOEY TPA: I think that’s a two-part question. To answer to the first part is this, opinions are like body parts, you know what I mean; everyone is going to have a different one. Objectively speaking, what you are hearing is neither right nor wrong because it depends on whom you’re hearing it from. Logically, some writers are going to share some bitterness because of the commercialism that graffiti has taken on nowadays. Maybe it’s because they see commercialism as part of that original establishment we fought against so long ago. I can’t blame them for their views but on the other hand it all depends on the direction that particular artist’s career, or hobby if you will, ultimately went. The irony is that history repeats itself and the younger writers share the anger we had back then too. Hopefully they mellow a little bit. I hope some of the old farts do too. There’s nothing worse than an old, grumpy-ass writer.

And that is a big difference right there, whether it was a career or a hobby. Graffiti was originally about “getting up”, that much I can say is true. The artistic values came into it when the cats with talent started popping up and taking their skills out of art school and onto the trains. Previously graffiti was something that was more about spreading your name around and graffiti by definition is public, hence The Public Animals. Graffiti is meant to be seen by the public, it’s art or statement for free and it’s usually covert, you know, done in the black of night or maybe boldly in daylight in a place most people would notice right away. Graffiti was meant to wake people up. Believe it or not, in a city of 6 million, a lot of them are the walking dead. Graffiti was an eye-opener. It gave the city officials something to bitch about and fight against. It made people think. Some got mad, some thought it was beautiful, others embraced it as a uniquely urban explosion seen nowhere else. In some ways it defined an aspect of city-living and the “art” of urban survival. That’s the origins of it. The beauty and the art came in through guys and girls who had mad talent and/or the need we all share to announce ourselves. But with that understanding, let’s get back to the question: is it a part of Hip-Hop?

You can’t stop evolution, some people try to stop or slow down progress, some people hate change. Hip-Hop was a part of a cultural revolution and massive graffiti was taking place at that same time. Rap for instance, didn’t really start coming about until 1976, ’77. Before that we had “MC poppin’”, basically just rhyming. You could be in the shower just rhyming, you could be cooking your breakfast and you rhymed. But rap itself formally came about in the mid ‘70’s and it came from uptown Manhattan and trickled all the way down to the south end of Manhattan through cassettes. It hit the East Village through guys that had a shoebox full of cassettes, and that’s how it migrated.

Graffiti, break dancing, rap and DJing all go hand-in-hand. They call this the “4 elements of Hip-Hop”. Three of the elements being more musical, and those three elements regularly used graphics by graffiti artists who were painting trains way before at least two of the elements caught on. They all went hand-in-hand as part of this larger phenomenon called Hip-Hop. It became pop, more fabricated, more managed and eventually appealed to investors. Anything can be painted in a negative or positive light but DJing is a business, and dancing, painting and rapping are all human expressions. All these little bits and pieces fell together at the same time. They all fed off of and supported each other. Of course graffiti is a part of Hip-Hop. It was around before “Hip-Hop”.

RIOTSOUND.COM: [laughs]

JOEY TPA: It just is. You don’t have to be a break dancer, a DJ or into beat music to be into graffiti. The coincidence is the shared urban heritage.

RIOTSOUND.COM: Over the past 30 years TPA has developed into a network of writers around the United States as well as around the globe. How did it make you feel, the fact that you were able to celebrate 30 years? And secondly, with the crew being so widespread these days, what is the common glue that keeps everybody together; is it representing for the TPA name, is it similar ideals, a somewhat common vision? Or is it just art in general?

JOEY TPA: It’s all with love and amazement, [that] is how I feel. 30 years went by very quickly. [Today] TPA is active in probably just as many countries as US states. It’s actually become more international than domestic, and the reasons that happened are many. TPA is legacy and that only happens over time; something doesn’t become legacy overnight. The fact that [TPA] has been showcased in publications around the world has given it an enduring life.

I would say the reason people want to get on board is that it’s an inheritance and people do like to be associated with things that are monumental. There’s a certain type of person who comes into TPA. They come through me because I fast to the original canon that made us from the very beginning. The glue is classicism. This crew was built on cautionary but open acceptance, not the arrogance of exclusion. It was built by three guys, each different yet respectful of the bond that brought and held us together. Our ability to reason and the mutual respect were what made us a stronger whole. That’s why there were only three of us at the core. There was never a tie and votes would be considered, but majority ruled. We were held together by a common bond which is acceptance and the love of this particular art form. That is what holds it together today. That same sweet formula is strong.

You go from Europe to countries in South America, to the States, down to Central America and back up into Canada and you’ll find TPA members that are all in touch with me. We disregard the barriers that normally keep people apart and distant. It doesn’t matter if you’re a professional or amateur artist, that’s not important to me. What matters is that fifteen year old kid who’s really hungry to be able to practice a certain type of art form, and to encourage someone like that. It’s about sharing and building

RIOTSOUND.COM: This Fall you will be launching a new clothing line, Street Level Nine, and you’ve stated that while the brand is aimed at the sophisticated consumer it also has its roots in graffiti as well as the urban lifestyle. Do you feel that your ability to develop a brand of this type, both sophisticated as well as Hip-Hop inspired, in effect speaks volumes to how the Hip-Hop generation has continued to evolve and is assuming a leading role within so many different facets of our society?

JOEY TPA: Well, we’re looking at Hip-Hop a part of American culture, in fact its world culture; same thing as the legacy of The Public Animals. You’re always going to have detractors, with success comes that mess.

Let’s face it, the American dream, the world dream, is success, whatever that means. We owe it to the younger generation to show them the good side of what can be done. Part of the growing process includes the responsibility to say, “We have changed and graffiti has changed; you can do it legally now”. Some guys are like – “nah, it should be illegal”. That’s foolish, especially if you have spent a lifetime building. At 50 years old am I going to go bombing trains and buses and trucks? No I’m not [laughs]. And I’m not going to tell younger guys who are fifteen or twenty years old to do it either. They’re probably gonna [do it] but they’re not gonna tell me about it.

We are lucky enough now to be able to make money out of it. Let’s just say you do it for free, there are places and situations where you can go to walls and paint without getting arrested. I wish we had that back in my time. On the other hand there was a thrill of doing things like trains. We really didn’t see this as hurting anybody. Maybe it was kind of like thumbing our nose at society and the establishment but there was no violence involved. Today both kids and adults have a chance to be able to express themselves in graffiti forms without facing danger.

Keep in mind that when graffiti was really coming about, the guys that did it were twelve, thirteen years old. Most of us quit at eighteeb, went off to the army, got married by the time we were twenty-one or twenty-two. Today you’ll see graffiti writers in their twenties and thirties, even forties.

Today writers buy spray paint. Years ago we didn’t buy spray paint [laughs]. If you bought paint you’d get a beat down for that. It was all part of the initiation rites. You had to prove your mettle. There are a lot of little things that I’d rather not get into but racking your paint was one of the fundamentals to becoming a bona fide writer. Today a dude goes out buys his paint and some guys from yesteryear might say, “man, that’s soft!” But you have look at [who is saying that]. Things change, hopefully for the better. Why steal when you can buy? Today you have these graffiti writers 25, 30 years old, they’re school teachers, they’re bus drivers, policemen, lawyers, and they’re part of the establishment. The kids look up to this. So along with that comes responsibility and setting the right example.

RIOTSOUND.COM: What are your goals for Street Level Nine clothing brand over the next year or so?

JOEY TPA: The brand is going to be a money-maker, but I have another reason also. It’s to show young people today that one of your legendary graffiti artists from yesterday who got mixed up in little things can achieve success also. I myself am no longer a practicing graffiti writer.

If you look around, you’ll find that every writer got a t-shirt line. SL-9 is strictly a cut and sew venture. The clothing itself might have little subliminal references to graffiti. For instance, you might see a zipper pull resembling an old subway token. My creative director is CANTWO, whom anybody in the graffiti world knows as one of the best graffiti artists on the planet. Coupled with a reputation like TPA has, success is right down the street but everything takes time. [SL-9] is not thug-wear, it’s more form-fitting, a little more sophisticated, a little more aspirational; something that is worn by a professional athlete or a professional actor on their down-time.

What you’re going to see in this line are classic looks, things that never get stale. You’ll see collegiate style lettering on a sweat shirt or a hoodie, but with contemporary imagery and fonts.

RIOTSOUND.COM: I know that when it comes to TPA’s membership you don’t allow any members of the crew to promote misogyny, violence or any other sort of negativity. Now, is that referring to someone’s character or artwork? Because there could be an artist that has good character but might portray violence in their art to make a point or bring attention to a certain issue; so where do you draw that line?

JOEY TPA: Well, art is a free form and I have the utmost respect for that above and beyond everything. You could have a great guy creating violent forms or a violent guy creating very tender forms which can be problematic when choosing. Typically, I don’t ask people to represent TPA, they ask me. The first I ask are for examples of their artwork. You can pretty much tell, after a few emails and phone calls what people are like. I also visit different countries and often meet artists that way.

RIOTSOUND.COM: Given the vast global nature of TPA, do you plan to employ the crew in bringing the SL-9 brand to various corners of the globe?

JOEY TPA: SL-9 is associated with TPA. I do separate them distinctly though. Just because someone is a graffiti writer in TPA doesn’t mean they’re associated with SL-9. There are people however who are willing to be supportive. So I let things kind of fall into place naturally. Street Level Nine is a creation from a person who was involved in the golden age of the graffiti era; therefore there is a natural correlation between the two, TPA and SL-9. That cannot be denied.

RIOTSOUND.COM: When we talked last you had mentioned how the early efforts to document graffiti culture by people such as Henry Chalfant and Martha Cooper as well as others focused a great deal on the Bronx but often neglected, perhaps inadvertently, the other boroughs. Why do you think that was the case and also can you characterize the nature of graffiti art outside the Bronx in that early period; how would you describe the styles and artists who emerged from say Queens or Brooklyn as opposed to the Bronx?

JOEY TPA: With all due respect first and foremost to the artists worldwide who respect the Bronx and to the Bronx itself, but through no fault of their own, any of these historical documents that chronicle the age of graffiti and its movement didn’t cover the whole thing.

The Bronx was certainly colorful because you had the infamous IRT lines going through there. The Bronx is a physical extension of Northern Manhattan Island, and also to Queens. It is a mixture of the deeply urban city coupled with the neighborhoods and bedroom community of Queens. It is connected to both regions by bridges and only 5 minutes away from either by virtue of these bridges. There is a lot of myth and folklore involved as there is with any complex social structure of such huge magnitude.

These movies and books did overlook the Queens and Manhattan areas as well as Brooklyn in their celebration of the infamous Bronx. Manhattan was vital, uptown Manhattan was even more central to Hip-Hop and graffiti. Queens, in fact, boasts some of the greatest kings of graffiti.

[As far as crews], you had the “big four”, which became the “big five” thanks to TPA. BYB, TC, TOP and NCB were the biggest crews of all time. They are respectfully known as the Brandeis (Bad) Yard Boys, The Crew, The Odd Partners, and lastly, the No Comp Boys. GREAT names for great crews, followed by the monster crew of all time, The Public Animals.

If you know your history, you will know that ALL if these five gigantic crews, while maintaining members in the Bronx, were founded and controlled primarily in and from Brooklyn and Queens. Sweet irony, isn’t it? BYB, Queens, TC, Queens, TOP and NCB, Brooklyn, TPA, Queens. There you have it.

WAR and WC were from Manhattan, as were TMB and RTW. The EX-VANDALS were from Brooklyn. But what does everybody remember because of the books that were published? They remember the bench at 149th [Grand Concourse subway station]. They remember Esplanade lay-up, Gun Hill Road; the names are very romantic but let’s not forget lower Manhattan, those layups. Let’s not forget the 7 Yard in Queens where every writer that was somebody would come out to hit.

Go to that original book The Faith of Graffiti by Norman Mailer and look inside that front cover and you’ll see a lot of names in there. I’m originally from Brooklyn myself. And then there’s the whole Brooklyn contingent.

Let’s not forget Welcome Back, Kotter, remember that sign at the beginning of the show?

RIOTSOUND.COM: I’ve actually only seen the show a handful of times…

JOEY TPA: Ok, well here’s a little history for you; when that show starts there’s a sign that says “Welcome to Brooklyn, the 4th Largest City in America” [laughs]… Brooklyn! That was 25 years ago when that show came out, I don’t know if it’s still the fourth largest city or not but I bet its right up there. My god, it’s HUGE!

I’m not trying to take anything away from the people who documented those books, who wrote those movie lines and those scripts, or the great artists and writers from the Bronx. I have the ultimate deepest respect for all of them but I just want to shed a little more light on the big picture. Enough already!

RIOTSOUND.COM: Also, just to give the readers some more insight into your own personal history as a writer; what were some of the different names you used?

JOEY TPA: My first name was PRESTO, I tagged JOE-188, JOEY TC. I wasn’t one of these guys who had 50 different names, which is so cool. I have to admit I envied those guys because they could actually get up with all those names.

I can’t believe it slipped my mind. I originally started out with ROCKET, I’m probably the first ROCKET and I shortened it when the mid ‘70’s came around and people started writing two letter names; those were the first real “throwups”. They were invented for speed and for the sake of getting up a lot. My two letter name was an abbreviation for ROCKET. That handle was RC. I think that before me, or at the same time, there were two other RCs. I believe it was RC-2 and RC-162. I started [writing] RC-3 and then I realized there was no RC-1. Then I also realized that RC-2 was a tagger, an inside guy, and I was the bomber; so I was able to drop the name down to just plain old RC. So when they talk about plain ol’ RC, they’re probably talking about yours truly.

I will always take my hat off to RC 162 and those guys because they’re real old timers. In fact, they’re probably older than I am. There’s a gazillion dudes named Joey and a lot of them tagged JOE or JOEY, but I think that on the record, when asked about it most people will point you in the direction of the one who was TPA, naturally. Just let me mention JOE 145 and JOE 136, those guys were first generation, my inspirations. I am second generation and I say that with all humility. I started in 1972 but I hit my first train in ’76 and guys like JOE 136 and JOE 145 were already established on mass transit by then. I’ve got a picture of a train where you see tags in chalk on the dusty outsides [Laughs]. I mentioned this on a radio talk-show about two months ago and some guy called in says, “well, that’s weak”. You know, back then before spray paint and markers you’d use your fingers, you’d get dirty.

RIOTSOUND.COM: I’d think you’d use anything you could get your hands on pretty much, right?

JOEY TPA: Anything, shoe polish, pencils, water markers, pens, even your finger nail; anything to get up. We’d use this chalk and believe it or not it stayed on really well. One thing I am really happy to say is that I was there to see it as well as be a part of it. I’m also pleased that you and I can talk to people about it so that they know the truth. Thanks!

For more info on Joe DeRoche aka JOEY TPA, check out www.MySpace.com/TPAProductions

Don’t forget to check out our TPA gallery, all pics courtesy of Joe DeRoche and TPA, click here.

Comments