by Alex Shtaerman

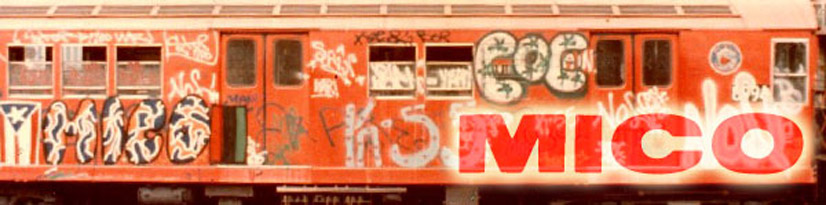

A key figure in New York City’s subway art movement, MICO started hitting trains shortly after his family emigrated from Colombia and came to New York City in 1969. An “original school” first generation writer, MICO is regarded among a select group of subway art pioneers that helped pave the way for subsequent generations of writers while laying the foundation for aerosol forms on a global scale. As a writer MICO became famous for his emphasis on the social and political themes of the day; while most writers simply wrote their names, as many continue to do today, MICO often sought to deliver a poignant message. Shortly after he began writing, MICO realized that New York City’s transit system presented much more than just an opportunity to get his name out. “This was the perfect vehicle for me to communicate my feelings or whatever else I wanted to communicate with the world through my work”, explains the artist; “especially on the subways which travelled all over the city”.

During the early and mid ‘70’s MICO staged a series of politically motivated and socially inclined transit art campaigns. By artfully writing slogans such as “Free Mandela”, “Free Puerto Rico”, “Free Lolita Lebron” and the infamous “Hang Nixon”, MICO tapped into the collective social consciousness of New York City commuters, injecting his own gospel into the urban landscape. A unique talent during aerosol art’s maiden era, MICO would also take part in some of the genre’s earliest exhibitions. In September of 1973 the Razor Gallery in New York City hosted the first formal exhibition of aerosol art; “MICOflag” by MICO was the first painting sold.

By 1975 MICO had all but retired from the subways leaving behind a lasting legacy, part aerosol art pioneer, part guerrilla social activist; a blueprint that would be revisited by many in the years and decades to come. Frustrated with the relatively short life his work had in the transit system, MICO increasingly pursued painting as an outlet for his self-expression. Inspired by the abstract forms of Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol he coined the genre of “Abstract Social Realism”, which he continues to work in today. In a recent interview we had a chance to catch up with MICO and talk about his career as a writer, the political slant of his artwork and much more. Insightful and entertaining, MICO definitely tells it like it is.

Click here to view some of MICO’s subway art as well as other works.

RIOTSOUND.COM: You moved from Colombia to New York City as an adolescent in 1969. When you first arrived in the United States, what was your initial impression; did you have any expectations of what the US would be like?

MICO: I had no idea what to expect because I was a 14 year old teenager. In Colombia my dream was to become a professional soccer player. My mom basically transplanted me – you know how you transplant a tree from one spot to another – [moving to the United States] was like a transplantation for me. When I got here what impressed me the most about the society here was how fast things were. Anywhere you go in the world outside of the US, the pace of daily life is just slower. So I was always impressed by that and I guess I eventually became part of this society. Today I’m an American citizen, my family’s here, my wife and my daughter are here. So now I do everything fast myself.

RIOTSOUND.COM: Especially being in New York City, that’s probably the fastest place in all of America…

MICO: Right, right, but interestingly enough I don’t become frustrated when I travel abroad or when I go to Puerto Rico, for example. I don’t get frustrated with the slow pace down there because I love that, that’s the place that I’m going to be retiring to in another couple of years; I’d much rather have a slower paced life. I want to take it easy because I’m going to be 53 this year so I’m no longer the young fast buck that I used to be.

RIOTSOUND.COM: Your career as a subway artist began shortly after you moved to New York. Right from the start you were very aware of various social and political issues which would often find their way into your work. When you first started writing you were still relatively young, where did your awareness come from?

MICO: Even before I got to the US I was very socially conscious and aware because I always loved to read the newspapers, from A-Z, I don’t know why, even when I was a little guy. And then when I got to the US, it was just at the end of the ’60’s, a very turbulent decade with civil rights and all that stuff; Vietnam was still going on. I’ve always been the kind of person where I like to investigate, I like to read and I like to research stuff, because I don’t practice believing everything I hear. So I try to get different sides of a story and form my own opinion about it.

[Early on] I became aware of the issue of Puerto Rico being a colony of the United States empire as well as the Cuba issue and all these other things. When I first started hitting – back in the original school of writing in New York City we used to call tagging “hitting” – I started hitting with my friends at Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn because we wanted to “become famous”. But eventually I realized this was the perfect vehicle for me to communicate my feelings or whatever else I wanted to communicate with the world through my work; especially on the subways which travelled all over the city. And that’s why you saw me [writing] a lot of things like “Free Puerto Rico”. I would have these campaigns like the campaign I did on behalf of the Five Puerto Rican Nationalists, the five political prisoners that Jimmy Carter eventually freed, Lolita Lebron was their leader.

RIOTSOUND.COM: You used to write “Free Lolita Lebron” at one point, is that correct?

MICO: Yes, that’s correct. I also used to write “Free Mandela”, “Free Walter Sisulu”, “Free Puerto Rico”, and “Hang Nixon”. With Tricky Dick, when he resigned in disgrace, it was [all about] “Hang Nixon”. Basically I was the first and only social-political writer of that original school, because everybody else was preoccupied with the top-to-bottoms and the bubble letters. Wild style was not available yet, until TRACY 168 introduced that later on. Everybody was preoccupied with killing and bombing and also some people used to do cartooning, which to me is not really writing because if you do cartoons you are a commercial artist, and I respect you for that if you do good work, but don’t tell me that you’re doing original work on the subways when you’re drawing Mickey Mouse or other Disney characters. Because that stuff belongs to somebody else, you’re just copying it, that’s not your original shit [laughs].

One thing that I always tried to focus a lot on was originality. I would always do a different piece every time I went bombing. That’s why I was not then, and I am not to this day, very impressed with the style of doing the same throw-up hundreds of times. I can recall the first guy who really started doing that in a mega way, it was IN. That motherfucker was doing IN IN IN IN IN IN, you know, the same letters, the same color, the entire car. What the hell was so creative about these things [laughs]? The only thing he was accomplishing was going over a lot of masterpieces done by a lot of other people, that’s what he was doing. But as far as myself, I was always focused on originality and doing a different piece each time.

One thing that I always tried to focus a lot on was originality. I would always do a different piece every time I went bombing. That’s why I was not then, and I am not to this day, very impressed with the style of doing the same throw-up hundreds of times. I can recall the first guy who really started doing that in a mega way, it was IN. That motherfucker was doing IN IN IN IN IN IN, you know, the same letters, the same color, the entire car. What the hell was so creative about these things [laughs]? The only thing he was accomplishing was going over a lot of masterpieces done by a lot of other people, that’s what he was doing. But as far as myself, I was always focused on originality and doing a different piece each time.

I never really carried any sketches with me because my stuff was in my mind, it was in my brain and it still is today. The brain is an incredible hard drive. What I would do is just pick my colors before I went on a bombing raid. For example, I would take two greens, three cans of red, four whites, six blacks; I had an idea of what I was going to do that night or that day but I really didn’t have a sketch or a piece of paper with me because, you know, it was just not my style. So that was a main focus of mine, originality, you will never find two MICO pieces that look the same.

RIOTSOUND.COM: By writing so many politically charged statements, your “Hang Nixon” campaign perhaps being the most famous of all, did you feel like you were most likely putting yourself out there for the authorities to come after you that much harder because of the things you were writing?

MICO: Absolutely, I was very conscious of that and that was part of my guerrilla war against the MTA. Eventually after many many years, after I had already semi-retired from writing I actually got busted with another writer in 1975 doing a series of clandestine murals around Manhattan. On November 1st, 1975 there was going to be a big rally at the United Nations in support of those jailed Five Puerto Rican Nationalists. The committee for the freedom of the Five Nationalists went up to the UGA [United Graffiti Artists] studio and they wanted to see if any of the writers at UGA wanted to participate in this campaign of murals to advertise the upcoming event at the United Nations. So me and another UGA member agreed to do it and on our second mural – we did the first one successfully – on the second mural we got busted. The Feds came down with albums full of mugshots of all the terrorists and all the communists [laughs]…

RIOTSOUND.COML: [laughing]

MICO: I’m telling you, we had a scary night, me and my friend…

RIOTSOUND.COM: What ended up happening?

MICO: What happened was that night they took us downtown and then the following morning the now deceased lawyer William Kunstler, who was like the most famous radical lawyer of the time [laughs], he walked into the courtroom, he approached the bench, spoke to the judge and then me and the other writer walked right out.

RIOTSOUND.COM: Wow!

MICO: Yea, it was a bullshit charge, you know, so nothing really ended up happening to us. But then another time when I was a full time writer, I think this happened in ’73 or ’72, I got busted by Detective [Steve] Schwartz, who at the time was the most famous detective of the MTA’s anti-graffiti task force. He had busted several of the big writers at the time. So the way it happened was me and SLIM 1, who was a Chinese youngster from East Flatbush, he was only 14 at the time, we had discovered the City Hall underground train yard where they parked a lot of really bright and clean RRs. Actually SLIM was the one who found the door and he suggested to me that there was a train yard down there, and I said – that’s impossible man, how can they have a subterranean train yard? And sure enough there was a whole fucking train yard there. So we went in there and it was great because it was like a train station underground but then it also had many tracks; you could stand on the platform and kill the entire car.

RIOTSOUND.COM: So no one had been there?

MICO: Right, I don’t think any other writer knew about that place at that time because there was no names on the walls, there was nothing there, it was all clean, it was unbelievable! But unfortunately for us they had a camera down there. And what they did is they sent down a uniform cop to chase us out. So when we saw him we ran into the tunnel and the next stop was Canal Street. So when we got to Canal, Schwartz and his partner, they were waiting for us. His partner, I forget his name right now, but he was a big Black detective; [later on] I heard his back got broken because someone pushed him down the stairs at the Ocean Parkway station. But to go back [a couple of years before that], the very first layup that I hit trains at was the Neck Road layup; Neck Road, Sheepshead Bay, that was my turf. That’s where me, MANI, MALO and others started.

RIOTSOUND.COM: You took part in some of the earliest exhibitions of aerosol art with Hugo Martinez’s United Graffiti Artists back in the early ‘70’s. When those exhibitions were taking place, how did you feel about what was happening? Was it something that you thought was just a stroke of luck or was there a sense of hope among the writers involved that this may lead to bigger things down the road?

MICO: [We were thinking about] the exposure and the fame. Remember, I told you we started hitting because we wanted to become “famous”. And now all of a sudden we are in this art gallery, the Razor Gallery. All the TV stations were there that day for the opening reception of that show. All the newspapers from New York as well as other countries were there. So it was really unbelievable. I said – holy shit, [laughs] we’re really famous now! But it had not sunk in yet, it did eventually. There were also negatives about leaving the underground and coming upstairs to the SoHo level. For example, when you hit a canvas it’s not the same feeling, and I emphasise the word “feeling” because there’s a lot of that involved here as far as feeling and soul, and it’s not the same feeling hitting a canvas. Even though you know you’re going to sell it for money, hitting a canvas is not like hitting a steel subway car that’s going to get your name all over the place.

The canvas will be purchased by some collector and that canvas is going to go into some vault or some room where the public is not going to be able to see it anymore. Over time, myself and other artists became aware there was a negative of bringing our work upstairs to the gallery level. However, personally I became discouraged about continuing to hit the subways because of several reasons. One of them I already mentioned, toys like IN that just came in to damage other people’s work. Also the city started buffing trains all the time even though we kept killing the trains again; and then of course the dangers of getting busted or even getting killed in the process. So I said to myself – you know what, I’d rather preserve my work and if I continue doing this in the subways it’s going to get buffed or it’s going to get crossed over by some toy. Why should I waste my time, my paint and my ideas if it’s all going to go to waste? So I actually became discouraged from painting on public subways mainly because of those aspects.

A lot of the young guys that came up, like third or forth generation [writers], although you gotta give them props because they did some [good things], but they really had no clue about doing the right thing. And doing the right thing is, of course, showing your work and giving someone else space and tolerating all of the other people’s rights to also show their work. I never went over anybody’s work. If I went to a layup or to a tunnel and there was a train where there was some bullshit on the side of the subway, like some small tags or whatever, I and others would consider that car to be clean for a masterpiece. So if you look at some of the photographs today you’ll notice that I did some MICO pieces where I went over somebody’s old signature or somebody unknown or whatever. But if I saw your masterpiece already there on the subway, I would never go over your shit, you know, ‘cause that’s crazy.

RIOTSOUND.COM: Over the course of your transit art career you spent a considerable amount of time painting in the Coney Island yard. That yard is so big, I always marvel at all the trains every time I drive past it on the Belt Parkway. During the time you were active, how important was it to hit the Coney Island yard?

MICO: The Coney Island yard was extremely important because of its size and because of the variety of different trains that they parked there. A lot of those trains became Ns, Ds, Bs, Fs, all kinds of trains. When the MTA switched around the trains, that was even better for us because we were getting more famous. If I hit a train that used to be, for example, a B train, and then all of a sudden it becomes an N train; well guess what, it’s now going to go Astoria [laughs], where the B train never goes. So [Coney Island] was a very important yard because of its size and because of the variety of different trains that they had there, definitely.

RIOTSOUND.COM: After you quit writing you moved more into painting and into a genre that you describe as “Abstract Social Realism”. Can you talk about that?

MICO: Abstract Social Realism to me is an extension of the work that I started to do on the subways. It’s always social-political, always trying to expose or communicate something that has to do with society, various injustices and things of that nature. But this time I guess it’s part of my personal evolution and my influence, having been influenced by all the artists who were not writers. I’m talking about the Picassos of the world and the Monets, the Warhols – from that the abstract bug got into me.

MICO: Abstract Social Realism to me is an extension of the work that I started to do on the subways. It’s always social-political, always trying to expose or communicate something that has to do with society, various injustices and things of that nature. But this time I guess it’s part of my personal evolution and my influence, having been influenced by all the artists who were not writers. I’m talking about the Picassos of the world and the Monets, the Warhols – from that the abstract bug got into me.

It took me a while to come up with the term and the concept [of Abstract Social Realism], about ten years I think, but then eventually in the mid ‘80’s I introduced this style with a piece I call “Colorful Curves”. After that I did [a piece called] “Very Colorful Curves” and then “Very, Very Colorful Curves”, it was a trilogy. And then I realized that I could depict, just like Picasso depicted any scene with little cubes and little squares and shapes, which he called “cubism”, it occurred to me that I could do the same. But instead of using block shapes, for example, I could use curves, and I figured I could call it “curvism”. To my surprise, when the internet arrived – research is so magnificent now with the internet – I realized that Picasso had used the term “curvism” way back when [laughs].

RIOTSOUND.COM: So you came up with the concept on your own not knowing Picasso also had a similar idea…

MICO: Right, right. But to me creating and painting is a lot of fun and it’s always about experimenting with things. I think that the social-political ideas should always be present [in the work] because painting is just like music and just like acting, you’re [conveying] something. I like to sometimes play with words or I may make up a name for one of my paintings that doesn’t exist in the dictionary. And then I also like to pick your brain, so when you see one of my pieces you really have to look into it to see what the hell is going on. I’m not going to give it to you that easy, I want to create a reaction in you when you look at my work. A reaction that’s going to be one of two things: either negative or positive.

Art really is about freedom, the freedom of the artist as well as the freedom of the viewer. So you have the freedom to say – you know what, this MICO painting sucks, I don’t like it, fuck it. And you know what, I will thank you a million times because you took the time to look at my piece and my piece accomplished what it’s supposed to do: create that feeling in you. In other words, I pushed that hot button of yours that made you feel that way. Or you can also say – you know what, this is a nice painting. And of course I would also thank you a million times for that. The idea is to awaken an emotion in the viewer.

RIOTSOUND.COM: For well over thirty years you have been active on the social-political front as an artist as well as an activist for certain issues that you’ve felt strongly about. What are some of the issues that still concern you today?

MICO: My brother, let me tell you, there’s so many issues [laughs]…

RIOTSOUND.COM: Yea… oh man… [laughing]

MICO: I’m telling you, if I didn’t have to go to my J-O-B every day, which will stop in another two years for me, I’m going to retire and I’m going to move to the mountains of Puerto Rico. Then I’m going to have the whole fucking day to do my work and my paintings. But if I had the full day [now], I have so many issues in my archives, both in my head and in my files downstairs. I have folders with newspaper clippings, with magazine clippings, I have video clips, stuff that’s just there waiting to be developed into a painting or maybe a sculpture. That’s another thing that I’m going to be getting into a little bit more than I have been, because I’ve done some sculptures but it’s not really a big thing for me right now.

But there’s so much stuff right now, with all the injustices that are going on, with all the abuses. For example, Amadou Diallo, 41 bullets; Sean Bell, 50 bullets, it’s always white cops as well as Black and Hispanic cops shooting at people of color. Because police racism doesn’t just come from white cops, police racism can come from Black cops [just the same], we call them “pigs” because that’s what they are. But they know where and what neighbourhood they can get away with shooting a citizen of that community 41 times or 50 times. I guarantee you that the motherfuckers that assassinated Amadou Diallo in the Bronx would never dare shoot a resident of Park Avenue and 59th Street 41 times because they know it’s a different community. So these assholes, they could be Black, they could white, whatever, it doesn’t matter.

But the racism is not really a race-related racism, it’s more like a social racism that exists. So that’s a major issue for me because innocent people are getting killed, you know. And it’s just depressing. So there’s many many issues, this war for example. Interestingly enough you and I are talking today on the fifth anniversary of this Iraq war, it’s unbelievable. So I have unlimited and infinite possibilities for creating artwork with the issues of the day and the times.

RIOTSOUND.COM: Do you have any message for the fans as well as any young people that may be reading this story?

MICO: Absolutely. Definitely stay in school but don’t believe everything that the school teaches you. Use the school as a platform for you to do your own independent investigations and research on the issues. Don’t earn a living illegally. Don’t go out there to commit crimes, to rob people or to sell drugs. Try to start your own business or get a job first, but most important, follow your dreams. If you discover what it is that you enjoy doing, whether it be programming computers or working as a carpenter or being a chef, follow that dream and give it all you got. And of course if you’re an artist, if you like to paint or if you like to draw, hey, more power to you. If you have to do it illegally, I don’t see anything wrong with that, but again, use that as a springboard for your career. Make it a career. Definitely stay away from drugs because drugs will cloud your mind, destroy your brain cells and there goes your talent. Drugs will kill you and your talent.

For more news and info on MICO stay tuned to www.MicoAsLatinPride.com

Comments