by Alex Shtaerman

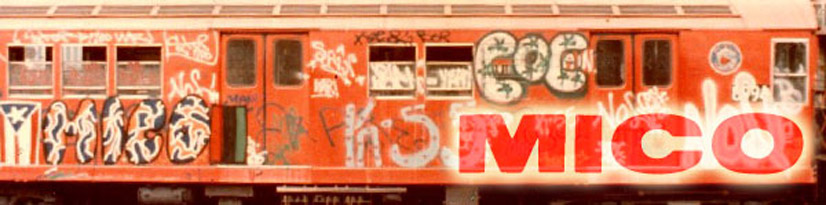

Lin Felton, known to many as his graff artist alter ego QUIK, played an integral role in New York City’s subway art renaissance. Painting trains through the ’70’s and well into the ‘80’s, he would garner all-city acclaim by relentlessly attacking NYC’s famed rapid transit system with thousands of pieces, throwups and top-to-bottoms; his name enjoying near constant circulation on tracks around the five boroughs for the better part of a decade. While bombing in an era of subway art legends, QUIK would carve out his very own piece of history and subsequently catapult himself into a lifelong career as an accomplished painter.His transition from the tunnels beneath NYC into galleries and museums overseas would begin in earnest in 1983 when an art dealer from Amsterdam by the name of Yaki Kornblit first came to New York looking for graffiti writers whose work he could exhibit over in Europe. Soon after, Mr. Kornblit would put on a string of extremely successful shows in his native Amsterdam featuring the work of transit system vets such as QUIK, SEEN, BLADE, DONDI and FUTURA 2000, among many others. Already in the midst of a largely unchecked wave of “creative vandalism”, the American influence would quickly send Amsterdam’s burgeoning graffiti culture into overdrive. The city would soon become ground zero in Europe’s street art movement as writers such as DELTA, SHOE and HIGH emerged to engulf the urban landscape with their handiwork.

Following his initial success with Yaki Kornblit, QUIK found himself traveling between New York and Europe almost every month to attend exhibitions featuring his work. As a market, Europe proved to be far more lucrative, and after shuttling back and forth for almost ten years, QUIK took up residence in Groningen, Netherlands in 1992. Since then he has continued to live and paint a continent away, making stops in the Netherlands, Germany and Paris; although no longer employing the rail system, his work continues to circulate. Featured in permanent collections as well as in frequent solo and group exhibitions, the NYC transit inspired paintings of Lin Felton continue to resonate with audiences over thirty years since a young QUIK first left his calling card on the side of a New York City train.

In the newly released Dutch graffiti documentary Kroonjuwelen: Hard Times, Good Times, Better Times (StunnedFilm), QUIK reflects on coming to Amsterdam and taking part in the Dutch graffiti scene following his golden era campaign in New York. Recently we caught up with QUIK to talk about his days “beautifying” trains, his views regarding today’s graffiti art as well as his time over in Europe. One thing is for sure, regardless of how long they’ve been away, New Yorkers stay New Yorkers. [Editor’s note: for more on Kroonjuwelen please check out www.Kroonjuwelen.com]

RIOTSOUND.COM: Back in the ‘70’s and early ‘80’s, when you were out bombing New York City trains, what would a typical night be like? For those who weren’t there to see how it really went down, can you explain what you would actually go out and do?

QUIK: Well, let’s say – one of my better partners was SACH and he maintained a huge amount of paint. SACH had the ability to acquire paint in large amounts and so did I. It [all] just came natural, like your daily chores, whether you’re going to school or to work you acquired your paint somehow, it wasn’t a difficult thing. So therefore our paint was organized – this [might be] a little difficult [to explain] – SEEN mentioned something to me recently, he said “Lin, one of the first times I met you, we opened the back of your car and you had a bag for the 6 Yard, a bag for the Es and Fs and a bag for the D train, you were so organized”. And, what truly impressed him was that [paint] was all for one night.

Guys such as SACH, DEMO 004, BIL-ROCK, REVOLT… we were very organized, sort of like military precision. You acquire your supplies, you pick the time that you’re going to perform your duty; get in, get out, get your name up or whatever you’re going to do [and] just get the mission accomplished. There were also a lot of joints involved, we didn’t drink a lot then. It was like a sport, you know, after work when [people] might go shoot hoops or whatever, for us graff was our competitive war-like exercise. Bombing just seemed normal. Writing was natural, it was something you did, something you had to do.

RIOTSOUND.COM: What prompted you to become so deliberate as far as how you went about your activities?

QUIK: Even when I was an early teenager, writing with groups of guys disturbed me. They would fight, they would be competing and groups were noisy. And, when you make noise is when one alerts the police. I didn’t want to play cat and mouse with the police. I didn’t want to taunt them, I just wanted to get my name up. So even when I was very young I would go writing with a very select group of guys who were perhaps older or just more mature in the act of getting the mission accomplished; guys like LIL SOUL, [also] VINNY.

I had a good experience in 1974 when this gentleman TRUE 2 took me to a layup in upper Manhattan. First we met up with a colleague of his and the writer said – ok, we’ll meet you at a [certain] time – say 1 o’clock on 168th street. We went to the tunnel and my buddy that day, he wanted to teach me. He said – QUIK you’re really bombing but I gotta show you how ‘cause you don’t really have it [down yet]. So we’re in the layup and TRUE is showing me to paint nicely, maybe that day I just did four pieces. Well, this other colleague [of ours] comes in and he happened to write JESTER. At the time this guy is king of the city! So JESTER comes in bombing, he paints with us and then he keeps going. When we finish our little pieces, well not little, but just what we had done that day, we leave the layup and I realize this guy [JESTER] has bombed every bloody fucking car in the layup just with his throwups. And then it clicked like – wow! that’s how you do it. THAT’S WHAT I WANT TO DO. He came in solo, said hello, bombed the shit out of [everything] and left. Bingo.

I didn’t need the social interaction, I started driving at a young age, so really I’d only see graff when I went to the tunnels or the yards. If I respected your work I’d paint next to you, if I didn’t like your shit I’d go over you. It was that king of the hill syndrome, but I did it [all] for me. I had some anger issues, clearly [laughs], so that’s the way I could work out my daily frustrations. And if I didn’t get over… I had two separate situations – once I went to a layup in the Bronx and wasn’t able to put my outline on [and finish my piece], I couldn’t sleep that night. I had gone home and I couldn’t fall asleep, so twelve hours later I drove back to the Bronx put the outline on the fucker and went back home and went to sleep. Another situation was at City Hall, I got chased in the daytime and I couldn’t sleep that night either. It’s like you didn’t get your orgasm. I [ended up] going back to City Hall, put the outline on and then I could go to sleep. I guess I need a psychiatrist for that.

RIOTSOUND.COM: [Laughs]

QUIK: [When I went out to do graff] I could trust myself to get the job done and I was very selective about the gentlemen that I would choose to run with. DEMO was one of my greatest partners, [also] KID 56 was an excellent partner and he’s a lot younger than me too. BIL-ROCK was also a good partner. HAZE for a moment was a good partner, he didn’t bomb that much but he knew what to do. I guess guys [I chose to run with] were just more intuitive about just getting the job done. REPEL was also a mentor for me, I hung with him in ’78, ’79, he showed me a lot of good ins and outs about getting up and getting over. Quite often he and I would get chased and have horrible adventures when we didn’t get over, so I learned from that.

I like to listen to guys like BLADE; if the guy did 5000 train pieces, he never got caught. And I look at bombing like it’s gambling, you know. You’re going against the system, you know the police are out there, there’s a ratio. I got caught four times and did thousands upon thousands of assorted pieces and throwups. So hey, that’s not too bad.

RIOTSOUND.COM: I had read that you once went over a BLADE and COMET whole car. For the sake of history would you mind filling us in on the details of that story?

QUIK: I like to tell that story sometimes in private [laughs]. But yes, REPEL had brought me to Esplande tunnels where BLADE and COMET bombed. So immediately I kept going back. And it was a good layup, you could get a lot of trains there. [So that day] I had gone there alone and I had been painting inside the tunnel for hours and when I came out of the tunnel the layup continued to the outdoors. And the whole way I’m walking, it’s six in the morning and no one is in the station, the birds are chirping, the early morning mist is swirling and dissipating, etc. I continue painting kind of out in the open and I come across a new BLADE and COMET on a freshly painted train. I proudly thought – wow! I’m in BLADE and COMET’s layup, they were here too but they didn’t come in the tunnel. And you know, these guys were my heroes, but yeah, this is the competition and I started going over it. Their brand new whole car, I started backgrounding it. And [the whole time] I’m thinking and knowing – these guys will kill me for this shit! I’m aware they’re big guys! And the funniest thing was, I’m getting to the end of my piece and I start running out of paint and then part of their names would have been sticking out. And I’m thinking – oh my god, these guys will hunt me down and kill me like the dog I am.

RIOTSOUND.COM: [Laughs]

QUIK: Somehow I got enough paint out of those cans, just squeezing and squeezing and I covered their car with my nice MOBY QUIK. Well, you know, my shit is ugly anyway but I felt SO good. Like, yeah, this is the game, who’s going to be king? Their [car] never rolled. And the anecdote to that [story] is when I first told BLADE about that he looked at me like – yeah, years ago we would have killed you! So he told COMET about it and COMET didn’t like the story so much. Years later in the ‘90’s BLADE and I had an appointment to paint canvases at my mother’s house. So I’m standing in the front garden and I see BLADE’s car turn the corner and then I see another car turn the corner, a big Thuderbird with a white guy. Oh shit! I just knew that was COMET.

RIOTSOUND.COM: [Laughing]

QUIK: BLADE and COMET then park their rides Starski & Hutch style, they come in and we hang out for about an hour. COMET meets me, sees my mother, sees my dog, but he’s kinda not feeling it, you know… hanging out with QUIK. And then after an hour of this tension, because I respect the guy so much, I mean c’mon, COMET is an all-time king. I said – listen, I have a six-pack of federal safety colors in the basement – and in my garage I had a nice QUIK on the wall. So I’m like – dude, how about I give you those cans and you get to cross out a QUIK for all the COMETS I went over. And he looked at me like – yeah, you little fuck [laughs]. And I’ve got action photos of COMET dogging my work in my house and the smile on his face is like a five year old getting a new tricycle!!! He was so happy by dogging this QUIK. [Back in the days] he and I went at it for a while on the 6’s, that was cute, but it’s just competition.

RIOTSOUND.COM: In the film Kroonjuwelen you talk about how you first met Yaki Kornblit and ended up going over to Amsterdam. What was your initial impression of the graffiti scene there? In what ways was it different from New York and also, in a general sense, how did you feel once you arrived?

QUIK: I didn’t look at it as something different. We were welcomed in a fantastic manner so everyone was friendly. Sure, people were writing on things; I didn’t kind of look at it like they had a certain [different] type of aesthetic. Maybe it wasn’t as developed as our stuff, but hell, I wasn’t that good anyway. I found the environment ripe for getting your name up. The entire city of Amsterdam was covered with graff so my work as well as that of the other guys fit right in. Of course ours was larger and you noticed it more because the manner in which we painted and tagged. [I would say the environment] felt fertile. As I had mentioned in the film, it had shocked me that the folks there wrote on those beautiful houses. They wrote on churches and cars ….Whoa!!!

RIOTSOUND.COM: As you say in the film, you were surprised how people in Amsterdam wrote on private property and even churches; in New York, people didn’t really do that. What do you think it was about the mindset over there that made that kind of thing acceptable? You would almost think there would be some kind of big public backlash to something like that.

QUIK: I guess they simply couldn’t help it and couldn’t control it. The kids were writing on your house, you’re pissed off and you paint over it. The same way we deal with crime here, crime is everywhere. If you know Joey down the block is an armed robber we don’t go and shoot Joey just to get him off the block, somehow you tolerate him. You just live with it. I found a distinct cultural difference when [I went to Europe and] I realized that my act of painting was very aggressive. If you fly me to Sweden tomorrow I’m not going to write on walls in Sweden because it’s beautiful. I don’t fuck up Paris and I’ve lived there for a year, it’s too beautiful for my horse shit. But if your entire city is painted, for instance the area I had lived in Germany in 2006, the whole town was ruined with graff, so why not? I’m bombing too! I ruined that town with my buddy SIL, we had a lot of fun. So if the property already has the shit on it then ok, then I’ll tag up. Amsterdam was ripe for tagging and also I had never been to a European city before, it had a different symmetry. So in order to venture out into the city I would tag and I could kind of follow my tags back to my hotel or my apartment where I was staying. It’s like dogs pissing, I left my sign and then I would follow the trail.

RIOTSOUND.COM: Graffiti art is obviously now a global phenomenon. At the same time we’ve also seen some of the older writers voice their displeasure at how graff has become commercialized, and in a lot of ways that has been the case. What do you think have been the pros and cons of how graffiti has developed over the last say ten years?

QUIK: The pros and cons of that, if we had a six-pack we could sit around and chew on that one for a few hours. A lot of people have a lot to say about that. I see it as a natural progression. It’s hip, it’s fun and sure, you can use a graffiti logo on your Crest toothpaste or on your soda can. It’s hip and it’s what people are doing. The dilution of it is just natural but then again I don’t worry about it so much. I’m really not that interested unless it harms my business. I’m well known for having painted trains, I paint canvas, I make drawings and it’s all in reference to the train painting person I was and it gives me a notoriety. I’m sure had I not painted the trains no one would be interested in my work but it [all happened] within a natural development.

I’m a painter, I’m not a “graffiti” writer any longer, I’m not a “graffiti” artist. I’m a black man who paints. When I get thrown into a category of a graffiti knucklehead – that’s why I try not to participate in exhibitions that highlight graffiti – I’m a painter. So I watch things change, I have a nineteen year old daughter, the things that she’s interested in boggles my mind. But I’m sure when I was nineteen or you were nineteen, our parents [also] thought, you know, what the hell is this? It’s what kids are into, so if there are 100,000 graffiti writers in specific countries, so be it. That doesn’t interest me unless it affects me.

Am I really concerned about any of it? Well, I like to look at the work sometimes. If I see a new innovative style or when I look at the French graffiti, I’m like, holy shit, those guys BURN! I mean, ok, [a lot of the artists] are wall painters, they’re muralists. It amazes me if my buddies GHOST and SAR send me a good black and white photo of a train from 1972 in New York covered with graff, that’s when I get really excited. I get truly turned on. I like graff on trains and I like New York trains. The visual aspect of this [new] aerosol art, it thrills me but [to me] it’s not like looking at an old train… there’s a big difference. In being a “QUIK” graff has opened many doors for me so I have to use those opportunities. Again, it can be disappointing for the fan base when they meet me and they say stuff like “hey, do you want to look at my black book?” No, why would I ever want to look at your black book?

RIOTSOUND.COM: [Laughs]

QUIK: [People ask] “hey, do you want to see my pieces?” No, why would I? Are they photos of New York trains that you did? Maybe I would be more interested if you show me your artwork and that lets me know more about you as a person and what you’re thinking. Any shithead can write on a train, anyone can. My ex-wife wrote on trains, big deal. I was working at a trade show out in California back in 1994 before all this graff and street wear really caught on and there was some downtime at the trade expo and I’m watching this girl, maybe she was eighteen, blond southern California girl, and maybe at the time she was working for the company Conart. She was drawing graffiti style lettering and b-boys better than anyone I had ever seen in my life. So here we have blondie from southern Cal, she had the flavor, she could do it. She could burn me easily. This is back in 1994. So anybody can do it [laughs].

RIOTSOUND.COM: Do you feel like some of the people, like say a Yaki Kornblit, who took the lead and put on some of those early graffiti art exhibits were ahead of their time and truly had the artists’ best interests in mind, or was it the case where sometimes the artists would get taken advantage of?

QUIK: A little bit of each. My experience with let’s say the Fun Gallery and Yaki Kornblit, it was done in good faith. They enjoyed looking at the work and they enjoyed exposing artists. Quite often when one realizes that they can make good money by performing a certain duty one becomes caught up in that cycle. Mr. Kornblit got caught up in that cycle a bit, yet the benefits of his money making abilities gave a group of us grand exposure as painters and as artists. You need a manager, one needs to be exploited to a certain point where you feel that it’s fair. I work in many situations where our relationships starts in good faith yet the person or company realizes how well they can pimp money out of my services and out of my performance, and then the relationship decays. Sometimes dishonesty and trickery [comes into play].

Dishonesty and trickery is inherent in the art world and its subsequent business. I find that only the richer dealers and clients are apt to steal my artwork or [at least they steal it] more often than someone else. They have the money where they can pay for it but they can slide a drawing or “miscount” how many paintings you left behind, stuff like that. It’s greed and megalomania but that can be a factor in any business. But usually it’s all in good faith. Quite often it’s a money making venture and if you’re mature enough you realize that these people only want to show your work because it’s trendy. So if you’re aware of that, you just simply have to protect yourself as an artist and as an independent person. And if you want to [do business with someone] you do it, if you don’t want to, just don’t do it. I end up rejecting many offers where the people want to show my work in good faith because I realize, hey, you can’t sell my work so I’ll get no money out of it. Sure you want to expose me but I also need to get paid. It’s time out of my life and it’s my business, so sometimes I have to reject the folks who just want to do it in good faith and choose the money makers who are just going to pimp my ass and try to make 400% profit. That happens, but as long as I’m aware of what I’m doing [I can accept it]. I don’t like it to be a surprise. If I sold you a painting for five grand and you sell it for twenty, if I’m aware, it’s ok.

When I was younger [aspects of how the art business worked] shocked me and at some point I moved to Holland to shut down the QUIK market a bit. I don’t want to mention any names but [other] guys were maybe having a hard time in New York. Even with making their thousand bucks [per painting] here and there, they’re living on the street, they’re on drugs and meanwhile these paintings are being sold for eight thousand dollars! So I’m thinking, well gee, now I’m aware and I’m going to stop that market for me. But that’s really unfair for that other guy because he doesn’t know [how much money is being made off his work]. It’s not my business to tell him but he’s living on the street. It’s just one of those things, you have to look at the art market, you know, it’s like the oil barrels. America and Britain took over Iraq but the price keeps going up. What a scam.

For more news and info on QUIK please check out www.QuikNYC.com

Comments